Mrs. Penfire Opens a Time Capsule

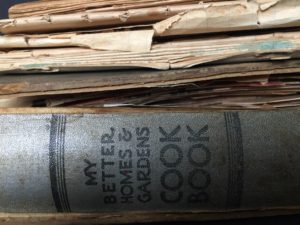

I recently discovered a time capsule hidden in a box on the back of a closet shelf—Great Grandma’s recipes. When my husband’s grandmother died in 1987, her recipe collection was handed on to me. An ancient My Better Homes & Gardens Cookbook (© 1930) so crammed with clippings, handwritten recipes, and various commercial recipe leaflets, that the cover had broken away from the binding.

My initial hope, in diving into this morass of brittled pages was to find out how to replicate the favorites Grandma had made for us when we visited her on the farm: the light-as-air rolls that always accompanied a dinner, and the shortcake she always served for dessert.

These recipes, alas, never surfaced. What I discovered instead was a culinary history that stretched back well over a century.

Born in the 1890s Ella Dot Martin grew up, an only child, on her parents’ farm in a Canadian village not far from the Vermont border. She married Sydney Blake, a distant cousin, and together with their two sons, the Blakes emigrated to Massachusetts, where they eventually owned and operated a dairy farm in Blackstone.

A Woman of Many Talents

A Woman of Many Talents

I knew and loved Grandma, who has always amazed me with her endless capabilities, interests, and spunk. For a farm wife in the first half of the twentieth century, there’s plenty of demanding work to be done, especially in a house with no running water, except for the hand pump at the kitchen sink.

But for Grandma, keeping house was just the beginning. She also kept chickens and ran her own egg business. (And if chicken was on the menu for a Sunday dinner, she would march over to the henhouse with her ax and quickly dispatch, pluck, and dress, the selected main course).

She sewed beautifully (we have a century’s old Christening dress to prove it) and was an accomplished musician. The organist at her church, she also played the piano for country dances, and at the local theatre—in the days of silent movies.

Know-How

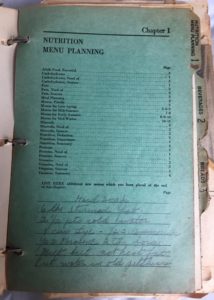

As I paged through Grandma’s Better Homes cookbook, I realized that she had written or pasted important recipes on its pages and section dividers. On the inside front cover, for example, I found a handwritten instructions that brought back vivid memories for Mr. Penfire. He told me Grandma had always mixed up pitchers of “Ginger Water” (and Kool Aid) for the men to take out to the field on hot summer days, when haying required hours of non-stop work.

As I paged through Grandma’s Better Homes cookbook, I realized that she had written or pasted important recipes on its pages and section dividers. On the inside front cover, for example, I found a handwritten instructions that brought back vivid memories for Mr. Penfire. He told me Grandma had always mixed up pitchers of “Ginger Water” (and Kool Aid) for the men to take out to the field on hot summer days, when haying required hours of non-stop work.

Imagine this drink: a tablespoon of ginger, 1/2 cup each of vinegar and sugar, 1/4 cup molasses–and water. Instinct tells me that this formula–and so many others among Grandma’s clippings and notes–exemplifies the practical wisdom that was handed down from one generation to the next. The reasons “why” something worked might have been lost–or never known. Yet the knowledge of “what,” “when,” and “how” had been well tested, and so was trusted.

A hand-written recipe for “Hard Soap” is mind-boggling. What is the purpose of a soap made of strained fat, lye, ammonia, kerosene, and borax. Surely, not a beauty bar!

Culinary Archaeology.

Grandma’s cache reflects the resources housewives of the day had access to–and how their interests (and the products available to them) changed over time. Her collecting days seem to have ended in the late 1950s. By then, she would have been nearly seventy years old.

Grandma’s cache reflects the resources housewives of the day had access to–and how their interests (and the products available to them) changed over time. Her collecting days seem to have ended in the late 1950s. By then, she would have been nearly seventy years old.

The 1950s. The biggest batch of clippings by far was from this era of glamorized kitchen tasks and the dawn of aggressive marketing for supermarket products. Grandma’s clippings, cut from newspapers and magazines included everything imaginable from casseroles, main dishes, one-pot meals and salads, to cookies, cakes, dessert bars and pies. There are multiple recipes for the same things— oatmeal cookies, date nuts breads, chiffon cakes, and many more.

The 1950s. The biggest batch of clippings by far was from this era of glamorized kitchen tasks and the dawn of aggressive marketing for supermarket products. Grandma’s clippings, cut from newspapers and magazines included everything imaginable from casseroles, main dishes, one-pot meals and salads, to cookies, cakes, dessert bars and pies. There are multiple recipes for the same things— oatmeal cookies, date nuts breads, chiffon cakes, and many more.

I came across more than a few full pages, neatly folded —magazine articles about the cure-all in your kitchen (ice) and newspaper sections devoted to “Chat.” Multiple leaflets indicate Grandma really fell for the marketing schemes cooked up by General Mills (creators of household heroine, Betty Crocker), Nestle (acquirer of Ruth Wakefield’s iconic Toll House recipe), Campbell’s and Lipton’s, (promoter of soup or soup mix as a secret ingredient) and even Franco American Macaroni and Cheese (don’t ask).

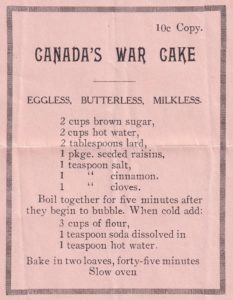

The 1940s. In Wartime, with basics rationed, it was important (and seemed patriotic) to make something out of nearly nothing. For example, a cake made of brown sugar, hot water, lard, raisins, salt, cinnamon, cloves, flour, soda, and more hot water. I couldn’t help wondering: Wouldn’t it be perhaps more of a treat to simply skip dessert?

The 1940s. In Wartime, with basics rationed, it was important (and seemed patriotic) to make something out of nearly nothing. For example, a cake made of brown sugar, hot water, lard, raisins, salt, cinnamon, cloves, flour, soda, and more hot water. I couldn’t help wondering: Wouldn’t it be perhaps more of a treat to simply skip dessert?

The 1920s and ‘30s. The Better Homes and Gardens edition of 1930 appears to have been the only cookbook Grandma ever owned. But she did keep and save numerous booklets from that era that were probably free. Among them, Home Canning Leaflet 142 printed by the Massachusetts Extension Service (1921). She pasted her own recipes of jams and preserves onto its pages.

The 1920s and ‘30s. The Better Homes and Gardens edition of 1930 appears to have been the only cookbook Grandma ever owned. But she did keep and save numerous booklets from that era that were probably free. Among them, Home Canning Leaflet 142 printed by the Massachusetts Extension Service (1921). She pasted her own recipes of jams and preserves onto its pages.

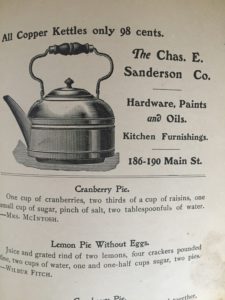

She also seems to have liked a community cookbook from Winchester, Massachusetts (covers missing) which featured, among the recipes, advertisements for local businesses, including a coal and ice company that also sold cook stoves, and a hardware store that offered copper kettle for 98 cents. She stashed multiple loose pages from older books, as well as hand written notes between its pages.

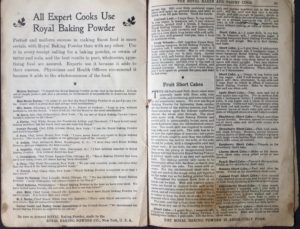

1911. The Royal Baker and Pastry Book includes a insert that assures any home baker that “All Expert Cooks use Royal Baking Powder.”

1911. The Royal Baker and Pastry Book includes a insert that assures any home baker that “All Expert Cooks use Royal Baking Powder.”

1890s. Grandma carefully saved fragmentary remnants of The Diamond Dye Cook Book, published around 1890. It appears to have been Canada’s answer to Fannie Farmer.

1880s. The oldest item in Grandma’s collection pre-dates her (she was born in 1890). My guess: it originally belonged to her mother-in-law, Mary Thomas Blake.  Not a cookbook at all, this is an 84-page section of a book that appears to be the minutes of Montreal’s Diocesan Convention 1882.

Not a cookbook at all, this is an 84-page section of a book that appears to be the minutes of Montreal’s Diocesan Convention 1882.

What a frugal innovation: to treat a printed book as though it were a scrapbook or notebook of securely bound blank pages. And so atop finely printed accounts of meeting minutes, resolutions, amendments and budgets Mary (or someone else) pasted the clippings and handwritten notes she wanted to keep safely in one place. (Perhaps this is how Grandma got the idea to do the same with her Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook, or perhaps this was routine practice for many farm wives who couldn’t just pop into the nearest Target to buy a blank notebook.

With no discernible logic to their placement, the clippings and handwritten instructions in this oldest “book” had titles like these: Cough Cure. Whiten Teeth. Fever mixture. Lineament for Sprains. Curing Bacon. Worm powder. Carpet Moths, Lice on Cattle—Rats. Dandruff. Pullet disease, A Cure for Mange on Horses. Make your hair curly and wavy overnight. (And on and on.)

On two of the unused back pages, I found “Sydney,” “Mary” and a few basic spelling words written in a childish scrawl. (Penmanship practice?). Sydney of course was the boy who grew up to be the man Grandma married.

The Need to Know

Grandma’s collection traces the slow evolution of necessary practical know-how.

In the pre-telephone days, when farm families might live a mile or two from the nearest neighbor–and many more miles from the nearest town–a housewife needed to know how to cope with just about anything.

What brought this point home to me more than any other was a folded paper with a paragraph written out in what I recognized as Grandma’s own hand. The first line reads “In cases of scarlet fever and diphtheria…”

What was it like, I wondered, when the best you could do for a child with a life threatening disease was ½ teaspoon brandy and ¼ grain of quinine?

Perhaps that question, more than any other, is testament to the value of exploring a time capsule. It’s easy to see what’s wrong in the world we live in. At the same time, it’s important to never lose sight of how very fortunate we are.