Many Questions. No Answers. Part V.

It has been a month since the death of George Floyd. Nearly two weeks since the death of Rayshard Brooks. Several months since the deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery. And the massive, widespread, worldwide demonstrations that were sparked immediately after Floyd’s death have continued unabated. Mobs of angry demonstrators are pulling down monuments, demanding removal of storied names from storied places.

A lot to learn

There are many who think these demonstrations are excessive, unfounded or unreasonable. I can’t help wondering how much they know about the long, painful history of African Americans. I know I don’t know as much as I could…or perhaps should. But I have read enough to understand why “Enough is enough” has become one of many slogans hand lettered on the placards some demonstrators carry.

If you’ve never read any books about black history, I have three to recommend:

If you’ve never read any books about black history, I have three to recommend:

Bullwhip Days – An anthology of oral histories in which former slaves describe the harsh and heartless realities of slavery. Commissioned by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, these first-person accounts are powerful, gripping, …and heartbreaking.

The Warmth of Other Suns – This book chronicles the Great Migration from the Jim Crow South to northern and western cities. It traces the stories of those who made that journey—what prompted them to uproot themselves and seek a better place to live, and the challenging new realities they encountered when they got to their chosen destinations.

The Warmth of Other Suns – This book chronicles the Great Migration from the Jim Crow South to northern and western cities. It traces the stories of those who made that journey—what prompted them to uproot themselves and seek a better place to live, and the challenging new realities they encountered when they got to their chosen destinations.

Just Mercy – A murder mystery, and also a real life example of just how unjust and merciless our criminal justice system can be. For this is the story of a black man who was framed, arrested, and convicted of murder, despite the clear and credible evidence that he was elsewhere when the crime was committed. His conviction was an expedient, really, because the community was clamoring for justice after the murder of a young white woman. But this of course was not justice. It was injustice—the kind of injustice that occurs all too frequently in America today. I have not yet seen the movie.

Just Mercy – A murder mystery, and also a real life example of just how unjust and merciless our criminal justice system can be. For this is the story of a black man who was framed, arrested, and convicted of murder, despite the clear and credible evidence that he was elsewhere when the crime was committed. His conviction was an expedient, really, because the community was clamoring for justice after the murder of a young white woman. But this of course was not justice. It was injustice—the kind of injustice that occurs all too frequently in America today. I have not yet seen the movie.

So here we arE

The anger has been building for years, decades, centuries.

“We have never honestly addressed all the damage that was done during the two and a half centuries that we enslaved black people.” This quote is from Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, who is also a professor at New York University School of Law. In an interview with Isaac Chotiner on The New Yorker website (June 1), Stevenson offers much insight into the experience of being black in America. “The great evil of American slavery wasn’t the involuntary servitude; it was the fiction that black people aren’t as good as white people, aren’t the equals of white people, and are less evolved, less human, less capable, less worthy, less deserving….”

“That ideology of white supremacy was necessary to justify enslavement and it is the legacy of slavery that we haven’t acknowledged.” Stevenson claims that “slavery didn’t end in 1865; it evolved….” When told they were finally free, black people “believed they would receive the vote, and the protection of the law, and land, and opportunity….” But the “ideology of white supremacy would not allow Southern whites” to fulfill these expectations. Stevenson believes that “you can’t understand…present-day issues without understanding the persistent refusal to view black people as equals.” The history of violence against black Americans has evolved. But underlying it all—from “terror and intimidation and lynching” to Jim Crow laws to today’s encounters with police that all-to-often turn violent—is a “presumption of dangerousness and guilt.”

It’s all too easy to blame the police

Unfortunately, society has cast the police in the role of oppressor. From the passage of Fugitive Slave Laws, well before the start of the Civil War, police were expected to track down slaves who had escaped to the north and return them to their “owners.” After emancipation, law enforcement turned a blind eye to the terrors inflicted on black communities. Between 1877 and 1950, in the American South, more than 4,000 African-Americans were lynched, most by hanging, although many were murdered in other ways—shot, burned alive, forced to jump off bridges, dragged behind cars. Law enforcement—police and the justice system—allowed this to happen, sometimes right on the courthouse lawn. Even into the 1950s and nineteen-sixties when nonviolent black Americans advocated for civil rights with peaceful demonstrations, they were battered and bullied by uniformed police officers.

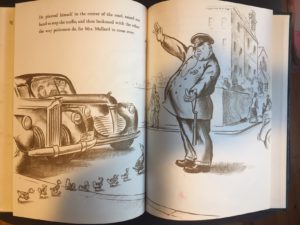

But simply blaming the police is a cop out (no pun intended) because police forces merely reflect the culture of the communities they serve. In many American communities today, police departments have come to see themselves as agents of control—as warriors rather than guardians. My own earliest impression of Police Officers was a benevolent combination of Michael—the rotund policeman of Make Way for Ducklings, who stopped the traffic on Beacon Street so Mrs. Mallard and her eight ducklings could get from the banks of the Charles River to the pond in the Boston Public Garden—and the pleasant young man I remember only as “Hank,” an officer in our town’s police force, who coached my brother’s Little League team.

My own earliest impression of Police Officers was a benevolent combination of Michael—the rotund policeman of Make Way for Ducklings, who stopped the traffic on Beacon Street so Mrs. Mallard and her eight ducklings could get from the banks of the Charles River to the pond in the Boston Public Garden—and the pleasant young man I remember only as “Hank,” an officer in our town’s police force, who coached my brother’s Little League team.

How times have changed. Towards the end of last week Mr. Penfire and I were sitting out on our tiny front porch in our rocking chairs. (A few days later from this very spot we would witness a car thief apprehended and arrested in our neighbor’s front yard and find ourselves both sad…for the thief…and grateful…for the police.) We had been called outside by our two younger granddaughters who occasionally come down the street to visit us (they live just a couple of blocks up the hill).

We never know when they will arrive—the eight-year-old on her bicycle, the six-year-old (who has turned seven) on her scooter. When the little girls come down, they stand outside shouting “Nana! Papa! Nana! Papa!” and we come out and take our seats. They perch on our fence—keeping a safe distance between them and us (during these days of coronavirus). We were all chatting happily when a police cruiser pulled to a stop in front of our house, just a few feet away from the girls. The officer got out and rushed towards our next door neighbor’s house. The younger sister slid off the fence saying, “I hope we’re not in trouble.” The older girl, retaining her seat, looked suddenly very sorrowful and worried. She looked at me and asked, “Did you know a police officer killed a man?”

I assured my granddaughters that of course they were not in trouble, that a police officer’s job is to help and protect us, that it was a very rare and terrible thing for a police officer to kill somebody—that the officer who had done that was a bad man who should never have been allowed to be in the police force, and that he would go to jail.

I keep thinking about my earliest impressions of policemen—the friendly helper—and those of my grandchildren—the scary enforcer. What a contrast!

Hope

So much of what I know about the lives of black people comes from reading. And no matter how much I read I cannot ever pretend to know what it feels like in to be in any skin other than my own. In his interview with Chotiner, Stevenson describes what it’s like to live in the skin of an African American: “There is this presumption of dangerousness and guilt wherever you go….the burden is on you to make the people around you see you as fully human and equal.” Having to navigate life in this way, day in and day out, Steven says, “you get exhausted.”

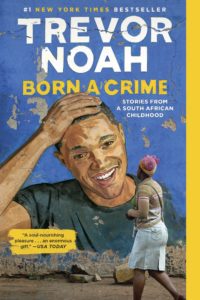

Last January the book group I belong to read and discussed Born a Crime, Trevor Noah’s memoir of growing up in South Africa, the child of a black African mother and a Dutch father. Noah’s parents’ relationship, the relationship that resulted in his birth was, in fact, a crime at the time. Thus, the title of his book. Noah paints a colorful, powerful and thought-provoking picture of what it was like to grow up with the burden that Bryan Stevenson describes. Even more telling, he relays a vivid sense of the ingenuity and pure guts it takes to find ways to thrive in a society where opportunities are denied and the only pathways open are dead ends.

Last January the book group I belong to read and discussed Born a Crime, Trevor Noah’s memoir of growing up in South Africa, the child of a black African mother and a Dutch father. Noah’s parents’ relationship, the relationship that resulted in his birth was, in fact, a crime at the time. Thus, the title of his book. Noah paints a colorful, powerful and thought-provoking picture of what it was like to grow up with the burden that Bryan Stevenson describes. Even more telling, he relays a vivid sense of the ingenuity and pure guts it takes to find ways to thrive in a society where opportunities are denied and the only pathways open are dead ends.

Noah was fortunate in having a mother who simply refused to carry the burden of unworthiness. She found her way around the barriers. When I read that this indomitable woman had managed to land a job that enabled her to earn a good living, a job that was available because of a special program that allotted a limited number of relatively good paying jobs to black South Africans, I couldn’t help wondering whether hers might have been one of the jobs that resulted from the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers protest I had witnessed decades ago. Ken Williams and Caroline Hunter demanded that the company they worked for (and I worked for) do something to change its business-as-usual arrangements in apartheid South Africa.

I hope it is so. I hope there is a clear link between that long-ago protest and the opportunity that enabled Trevor Noah’s mother to have a decent paying job. Because that would mean that progress towards justice is possible. That would mean: There is hope.