The Battalion Artist at Stanford

September 12, 2024 The last time I had seen Nat Bellantoni’s watercolors and sketchbooks, the photographs, documents, official handouts he had brought back from his World War II deployment in South Pacific, the books, videos, and videotapes he had added to his collection over the years…it was October of 2017. I was helping my friend, Nat’s daughter, Nancy, sort and organize it, creating dozens of packages wrapped in acid-free paper and carefully labeled. Within days it would be shipped off to the Hoover Library and Archives at Stanford University.

The last time I had seen Nat Bellantoni’s watercolors and sketchbooks, the photographs, documents, official handouts he had brought back from his World War II deployment in South Pacific, the books, videos, and videotapes he had added to his collection over the years…it was October of 2017. I was helping my friend, Nat’s daughter, Nancy, sort and organize it, creating dozens of packages wrapped in acid-free paper and carefully labeled. Within days it would be shipped off to the Hoover Library and Archives at Stanford University.

As Nat had requested, Nancy I had put together a book, which the Hoover Institution Press published in 2019.

In the book’s introductory pages, Eric Wakin, Director of the Library and Archives, called this treasure trove “perhaps our richest collection to date documenting the reality that US naval construction battalions faced as they fought disease, harsh climates, and armed enemies to build airfields, docks and barracks for the millions of American fighters crossing the Pacific Ocean during the Second World War, headed to Japan.”

There was a plan for an exhibition as a follow on to the book’s publication. But then: COVID struck. Ever creative, the exhibitions team came up with a wonderful online exhibition. https://histories.hoover.org/battalion-artist/

Then, finally, the COVID restrictions were lifted, and the gallery exhibition at the Hoover Tower became a reality.

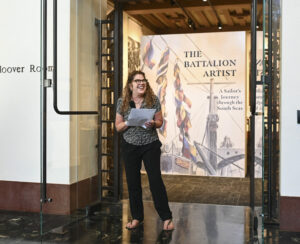

The Opening was September 12, 2024, and Nancy and I were privileged to speak about our project, The Battalion Artist book, precursor to The Battalion Artist exhibition. Director Eric Wakin introduced us, providing context and his expert perspective.

Nancy’s Remarks

I would like to begin by expressing my sincere thanks to The Hoover Institution. To Eric, for realizing the importance of this collection. To Jean Cannon and the team of superheros, Samira, Kiera and Marissa who put together this dream-come-true exhibit of my father’s WWII collection.

The Battalion Artist: chronicles the wartime experiences of just one man, my father, Nat. And yet, it reflects the story of an entire generation. More than 16 million men and women served in the US military during WWII.

350,000 of them, like Nat, were Navy Seabees. I had the honor to meet some of them as I accompanied my father, then in his eighties, to reunions of his 78th Construction Battalion in various states. These generous, strong, men were proud of their service to their country and to the world. This exhibition is my father’s tribute to them, and to all that they accomplished.

Nat left Massachusetts College of Art in the fall of 1942, joined the Navy, and eight months later found himself in the South Pacific. Constantly vulnerable to enemy attack, living and working in a bizarre jungle environment, and forever longing for home, he turned to the coping mechanism he knew best. He created a visual diary.

Nat instinctively knew the best way to manage the narrative of his life, and to cope with the ups and downs of his feelings, was to create images. Sketching and painting allowed him to share his observations, ideas, and emotions with the people he cared about. More important, the quiet work of transforming ideas into images transported him to a realm of inner peace.

Nat’s paintings tell us the story of his service. They allow us to see and feel the colors and textures of wartime life through the prism of a curious and creative young man. He painted what he saw, it was his passion not his job. His subject matter was his daily life; endless days at sea, harbors and ships, men at work, air strips, the local countryside and the view of enemy planes overhead at night from his fox hole.

Among his varied tasks, my father worked closely with the battalion’s photographer and writers to create the 78th’s Battalion Log, as well as the daily newspaper, Tractor Tales. A compulsive archivist his whole life, he kept at least one copy of every photograph snapped by Ed Keegan, documents– both official and unofficial, handouts and mementoes—as well as gifts from native islanders.

Seventy-five years later, when Janice and I began to plan how we would create Nat’s book, we had paintings, sketchbooks, letters to the love of his life, Irene, over 600 photographs, and other treasures that he had saved in unmarked boxes. Sitting in my living room surrounded by all this, Janice and I realized that our objective was not just to write about Nat’s paintings, but to insert all these priceless items into a timeline of history, of war in the Pacific.

This is the story of one brave young man. This is also the story of a young woman. Irene Sztucinski, my mother, who completed her studies at Mass College of Art and got a job. She lived with her parents, socialized with family and friends. And waited, worried, hoped and feared.

She rushed to the mailbox every day, because a letter from him made his presence real for her—for at least those moments in which she was reading, or re-reading it. She never knew where he was, on Island X, somewhere in the South Pacific.

This exhibit explores three years, three months and three days of Nat Bellantoni’s long life. Irene is off-stage throughout. Yet in truth, she is present at every moment. For without her love, her letters, her willingness to put her life on hold while he was away, his life story might have been quite different. Because the art he created in the South Pacific was, essentially, for her.

And the making of it is what sustained his spirit.

While in hospice care at home, at the age of 91 my father told me that he wanted to write a book about his paintings. “You better hurry up!” I said.

We had the paintings, and together we had gone over them one by one many times. These are all on view. Nat created them while at sea and on the islands of New Caledonia, New Guinea, the Admiralties, and Okinawa.

“I can design the book. I’m not a writer though, maybe Janice will write it,” I suggested to him in reply. “Okay, but don’t get carried away, you two,”

he said.

And so I emailed Janice.

My Remarks

I had known Nat since my very first job as a young copywriter.

I worked at Polaroid Corporation, and Nat was an art director for a firm that did a lot of work with us. He helped me—and everyone in my department—with the graphics needed for our projects. He was always in and out of the Art Department, which was right next door to my office. So several times a week, I could count on a smile, a wave, and friendly hello from Nat. That’s the kind of guy he was.

When I got that email from Nancy back in June of 2012, I knew Nat was 91 years old and failing; I was expecting the worst. I was not expecting to hear that Nat wanted to write a book. “What should I tell him?” she had asked me.

“Tell him we’ll do it,” I wrote back. “Of course.”

A few weeks later Nancy and I sat down in her living room surrounded by all the source material she has described—and of course the paintings. I quickly realized just how daunting this project was going to be.

We needed to know where Nat was when he made each of these paintings, what was happening around him, and what was happening with the War. We needed to put him and his paintings in context.

Nat had provided exactly what we needed to get started:

A list of the paintings in chronological order, with a title and brief description of each.

The Battalion Log. A summary in words and pictures of what Nat and his fellow Seabees had experienced.

And a dictionary-sized book: “Building the Navy’s Bases in World War II” the Navy’s official record. Nat had tagged the pages that described the projects completed by the 78th Construction Battalion

We also had all the photographs, documents, and memorabilia Nancy described—much of which you’ll see in the exhibition.

Nancy’s job would be to comb through all this material and choose the images we’d use in the book. My job was to write it. And to do this I had a lot to learn.

I spent a whole year reading, underlining, and taking notes from many of the excellent histories of the War in the Pacific…

…along with the two classic accounts of the Seabees’ in World War II: Can Do! And From Omaha to Okinawa.

We created a timeline of the 78th’s deployments, from one island X to the next. As I began to match up the progress of the War with our timeline, I would be stunned to discover that Nat had been in the thick of some quite terrifying situations.

I would call Nancy and say: “Did you know that when your father was in Finschafen, New Guinea, the battle was only five miles away?”

Or, “Did you know that when the first echelon landed on Los Negros they had to set up a perimeter on the beach to defend themselves and their supplies?”

Or, “Did you know that when Nat landed on Okinawa the men had to step over dead bodies to set up their tents?”

And of course she didn’t know any of those things. Because like most of the men who came back from World War II, Nat kept the worst of it to himself.

As Nat’s story began to take shape in my mind, I felt it was important to figure out what he and the other Seabees would have known about the progress of the war. They knew a lot. They paid close attention and shared any news that came their way.

They knew when ships went down. And so, every time they had to board a transport, they understood the peril. They were as just vulnerable as their fellow sailors on fighting ships.

This knowledge is reflected in several of Nat’s paintings.

Because the Seabees built and maintained airfields, they were constantly watching the comings and goings of aircraft.And they were well aware that when planes took off, not all of them came back.

Nat’s most treasured painting reflects that awareness. It’s the portrait of PBY 50, on the cover of The Battalion Artist.

In writing this book, my biggest challenge was not the research, or creating the narrative that took Nat from Boston to Port Hueneme and back. No. My biggest challenge turned out to be the essays that accompany each of Nat’s watercolors. I worked on these essays one by one. Taking some pretty long breaks in between.

Each time I sat down to write, I would stare at the painting, then at the blank document on my computer screen.I would sit and ponder. What had prompted Nat to create this image? What was happening around him? What was he seeing?Thinking? Minutes would go by.

Images would swirl in my head. Nat’s handwritten letters to Irene. Ed Keegan’s black-and-white photographs. These became so familiar I could easily retrieve them in my mind’s eye: Bulldozers and trucks moving among walls of dense vegetation. Men toiling. Sailors standing in a makeshift chapel, their sweat-soaked backs to the camera. Native islanders looking on watchfully from their outriggers.

After a while, I would begin to type. Once I started, the descriptive commentary seemed to write itself. I didn’t stop typing until I got to the end. Then, without even reading it, I would send the essay to Nancy.

After a while, she would fire back an email saying: It’s perfect. How did you know what to write?” And I would reply, “I don’t know. I guess Nat must have told me.”