Pandemic fatigue

Why did we think that we would escape the kind of historic cataclysms that have upended the lives of every generation? Think of our parents. And grandparents.

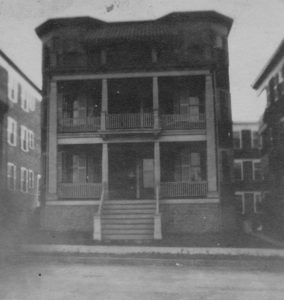

I think of my grandmother. First cataclysm: Flu epidemic of 1918. Mary and Phil Flynn lived in the first floor apartment of a brand new triple-decker on Morton Street in Boston’s Mattapan neighborhood with their four young children ages 9, 7, 5, and 3. How to protect them? Grammy tied bulbs of garlic around their necks. Death was everywhere. My mother (age five a the time) remembered seeing caskets stacked up on the sidewalks. The young couple who lived on the third floor had a baby; then the new mother caught the flu and promptly died. The young father was frantic. No relatives would come near the house to help him. My grandmother took charge; she would care for the baby so the father could go back to work. This arrangement continued until 1921 when the Flynns moved to South Weymouth, where two more boys were added to their family.

First cataclysm: Flu epidemic of 1918. Mary and Phil Flynn lived in the first floor apartment of a brand new triple-decker on Morton Street in Boston’s Mattapan neighborhood with their four young children ages 9, 7, 5, and 3. How to protect them? Grammy tied bulbs of garlic around their necks. Death was everywhere. My mother (age five a the time) remembered seeing caskets stacked up on the sidewalks. The young couple who lived on the third floor had a baby; then the new mother caught the flu and promptly died. The young father was frantic. No relatives would come near the house to help him. My grandmother took charge; she would care for the baby so the father could go back to work. This arrangement continued until 1921 when the Flynns moved to South Weymouth, where two more boys were added to their family.

Second cataclysm: The Great Depression. Phil was a printer by trade. Fortunately, the company he worked for published railroad timetables, which had to be updated regularly. “If I can get just a couple of days’ work each week,” he used to say, “we can get by.” And they did. Grammy’s ingenuity helped. She planted a garden, canned vegetables and fruit, kept chickens. She marched her children through the nearby woods to gather wild blueberries, then sent them door to door to sell the berries, ten cents a pail. In winter it was wreaths, made from the greens gathered in the same woods. The young sales force might have been reluctant, but what choice did they have? There was no saying “No” to Ma. Third cataclysm: World War II. Shortages. Rationing. Those were inconsequential annoyances to Mary and Phil. Their concern was their four sons. Joe had joined the Navy for a six-year hitch in 1940. John signed up for the Army. Philip, the youngest, lied about his age to volunteer for the Army Air Forces. Meanwhile, George (married with three children) was called up despite his age (32); he served with the Navy’s United States Fleet Post Office in New York.

Third cataclysm: World War II. Shortages. Rationing. Those were inconsequential annoyances to Mary and Phil. Their concern was their four sons. Joe had joined the Navy for a six-year hitch in 1940. John signed up for the Army. Philip, the youngest, lied about his age to volunteer for the Army Air Forces. Meanwhile, George (married with three children) was called up despite his age (32); he served with the Navy’s United States Fleet Post Office in New York. Three of four sons were overseas, their parents knew not where. Grammy, a woman of action, wanted to do whatever she could for her boys. So, when Joe wrote saying the men on his ship had adopted a little dog, she knit a sweater for the sailors’ mascot. (How was she to know Joe’s ship was installing submarine nets in the Caribbean? No need for a sweater in that climate.) John was the son Grammy probably worried about most; he was the quiet one. How to cheer him up? She would send him his favorite dessert. Imagine what cream puffs must have looked like by the time they reached John, serving with the 349th Infantry in Italy. Ever after, the family joke was that John’s best bet with those cream puffs would have been to use them to kill Germans.

Three of four sons were overseas, their parents knew not where. Grammy, a woman of action, wanted to do whatever she could for her boys. So, when Joe wrote saying the men on his ship had adopted a little dog, she knit a sweater for the sailors’ mascot. (How was she to know Joe’s ship was installing submarine nets in the Caribbean? No need for a sweater in that climate.) John was the son Grammy probably worried about most; he was the quiet one. How to cheer him up? She would send him his favorite dessert. Imagine what cream puffs must have looked like by the time they reached John, serving with the 349th Infantry in Italy. Ever after, the family joke was that John’s best bet with those cream puffs would have been to use them to kill Germans.

No telephone calls back then. No emails. So my grandparents waited for letters, which arrived only sporadically. And when a letter did arrive, how much assurance did it truly offer? He was alive and well when he wrote this, perhaps weeks ago. But what about today? Apprehension must have been an underlying reality of every waking moment. Would this be the day a fateful telegram would be delivered? The worry must have been crushing. And it was crushing for my grandfather, who took to bed with an undefined illness—perhaps lead poisoning from a lifetime of contact with printing ink, the doctor suggested. Phil more than once woke up screaming, “The ship’s going down!” He died in October of 1943.  Once over the initial shock and grief, Grammy, at age 59, began figuring out how to support herself. She already had a small business going. The sign to the left of the driveway of the Flynns’ small Federal-era white frame farmhouse attested to that: “Yarn Shop.” Grammy thought nothing of driving to Bernat Mill in Uxbridge for supplies (a hundred-mile round trip ). She sold her own hand-knit sweaters, hats, and mittens, as well as knitting supplies. Her most profitable items? Probably the multi-colored afghans she made from tangled odd ends of yarn, bought (for next-to-nothing) by the boxful.

Once over the initial shock and grief, Grammy, at age 59, began figuring out how to support herself. She already had a small business going. The sign to the left of the driveway of the Flynns’ small Federal-era white frame farmhouse attested to that: “Yarn Shop.” Grammy thought nothing of driving to Bernat Mill in Uxbridge for supplies (a hundred-mile round trip ). She sold her own hand-knit sweaters, hats, and mittens, as well as knitting supplies. Her most profitable items? Probably the multi-colored afghans she made from tangled odd ends of yarn, bought (for next-to-nothing) by the boxful.

Ever practical, Ma decided to take advantage of the demand for housing created when the massive South Weymouth Naval Air Station was built practically next door—occupying the very fields and woods where her family used to gather blueberries and Christmas greens. Workers on the Base needed housing. Her boys were away. Why not rent out their rooms? Thus, when Philip, her youngest arrived home on leave, he was in for a surprise. “You’ll have to go sleep at Uncle Dan’s,” his mother told him (Uncle Dan lived only a few blocks away.) “Your room is rented.”  Grammy Flynn was, for sure, a no-nonsense woman. She met life’s challenges head-on. She survived the Flu Pandemic of 1918, the Great Depression, and World War II (and though she had lost her husband, she considered herself very lucky to have all her sons return home safely).

Grammy Flynn was, for sure, a no-nonsense woman. She met life’s challenges head-on. She survived the Flu Pandemic of 1918, the Great Depression, and World War II (and though she had lost her husband, she considered herself very lucky to have all her sons return home safely).

I often wonder what Grammy Flynn would have done during these many months that our lives have been turned upside down by COVID-19. Would she have complained about pandemic fatigue? I doubt it. I think she would have used the time to knit up a storm. She would have been sensible about social distancing. She would have been conscientious about washing her hands. She would have worn a mask.