Operation Magic Carpet: Veteran’s Day, 1945

Recently, we marked the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. But in fact, for most of those who had done the fighting, the War did not end on September 2, 1945, because they were still in uniform and very far from home.

Veteran’s Day, November 11, 1945, found more than eight million soon-to-be-veterans stranded overseas. Among them was Nat Bellantoni; he had left art school in Boston to join the US Navy’s 78th Construction Battalion—one of the legendary CB (Seabee) units that built the bases, airfields, and docks that fighting forces needed. Nat, now 24, had been in the South Pacific for nearly two and a half years.

Nat, now 24, had been in the South Pacific for nearly two and a half years.

Serving on the South Pacific’s Equatorial Islands meant sweltering heat and suffocating humidity—living in tropical jungles dense with rotting vegetation, biting bugs, swarms of malarial mosquitoes, all manner of exotic birds, rare bats, rats, lizards, and snails, amidst a population of native islanders still adhering to ancient ways. The annual monsoon months—December to May—brought torrential rains at least once a day, every day, deep mud, flooded tents, and perpetual wetness.

If discomfort was ever present, so was unspoken, unacknowledged fear. For every man knew that the next air alert might be his last. Underlying all, the helpless, hopeless, empty gnawing of homesickness

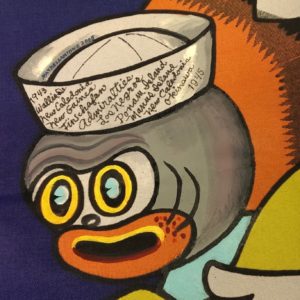

Whenever the Seabees completed work on one island, they moved on to another. There would be tense days at sea, lookouts and gunners scanning the horizon for enemy planes and ships. The Seabees were never told where were headed. Always, their orders read: Island X. (Years later, on the cap of the Seabee that graced his 78th U.S. Naval Construction Battalion Flag, Nat Bellantoni would carefully inscribe the names of all the island bases on which he had found himself during his years in the South Pacific.)

Whenever the Seabees completed work on one island, they moved on to another. There would be tense days at sea, lookouts and gunners scanning the horizon for enemy planes and ships. The Seabees were never told where were headed. Always, their orders read: Island X. (Years later, on the cap of the Seabee that graced his 78th U.S. Naval Construction Battalion Flag, Nat Bellantoni would carefully inscribe the names of all the island bases on which he had found himself during his years in the South Pacific.)

For Nat, the final Island X was Okinawa. There, alongside more than forty other Seabee Battalions, the 78th worked to build the massive advanced base from which the invasion of Japan would be launched.

And then: two bombs destroyed two Japanese cities. And the war was over.

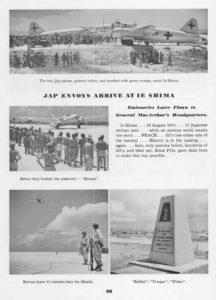

Nat and the Ed Keegan, the battalion photographer, were sent from their camp at Bolo Point to the nearby island of Ie Shima. There, on behalf of all those who had served in the Pacific theater, they witnessed—and recorded—history: the landing of Japan’s surrender delegation and their transfer to an American C-54 Skymaster that would take them on to Manila.

The war was over! Nat had survived it. He was flooded with emotions. Joy. And sadness, too, for the countless others who had not lived to see this day. But most of all, relief.

Now he knew for sure that he would be going home. All he wanted was get there—to wrap his arms around his mother, his father, his sister, his brother. And most of all, his sweetheart, Irene. But he would have to wait.

OPERATION MAGIC CARPET

Nat and millions of others at bases scattered all over the globe were in the same boat. Well, actually, they were not in any boat, and that was the problem.

There simply weren’t enough ships. Troops had been sent overseas gradually over a period of three and a half years. Transporting them back to the States all at once was impossible. The War Shipping Administration—in charge of this massive endeavor—did its best, commandeering every available vessel.

Tankers, freighters, battleships and aircraft carriers were all converted to accommodate as many men as could be squeezed aboard. The lucky guys were crammed onto luxury liners. In fact, they all felt lucky.

Who got to go home first? There was a point system. “Home Alive in ‘45” was the goal, but meeting it would prove impossible. Set in motion on September 6, 1945, Operation Magic Carpet transported an average of 22,222 Americans home every day for a solid year.

As Nat awaited his turn to head home, he puzzled over what to pack—his sketchbooks, drawings, and watercolors, of course. But also, his unique role as battalion artist left him in possession of hundreds of photographs and documents—a primary source for future historians. Nat was determined to leave none of it behind. He had a sea chest that one of the carpenters had made for his art, and he filled it to the brim.

On November 5, 1945, Nat’s orders came. He conveyed the news to Irene on a V-mail form, writing in the header: “OH JOY OH BLISS OH HAPPY DAY.” The next day, he was finally on his way back to the woman who would soon be his wife.

VETERANS DAY

VETERANS DAY

Today, November 11, we honor the valiant Americans who have served in all wars. Let’s take a moment to think back 75 years—to those who had recently come home and those who were still waiting to return. They helped save the world. A world that today is suffering from a pandemic. They protected our freedom and our democracy. A democracy that today is experiencing unprecedented political strife. They fought for us—their children, their grandchildren, their great grandchildren.

Let us show our gratitude for all that they sacrificed. Let’s each one of us do what we can to protect ourselves and each other from the pandemic. Let’s do what we can to end our country’s pain. Let’s fend off hatred. Let’s work to ensure that this democracy works as it should. Let’s make our country and our world a better place.

https://histories.hoover.org/battalion-artist/

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-magic-carpet-1945