BETTER? OR WORSE?

It is disheartening, to say the least, to sit down at the kitchen table with your first cup of coffee, scan the headlines of your morning paper, and see that one of your favorite places—and favorite views—overlooks a toxic waste dump.

That was my experience this morning, and I am still trying to wrap my head around it.

That was Then

I was a child in the early days of television. Our black-and-white set was a Philco—a small (12-inch) picture tube housed in a walnut cabinet the size of a small dresser. There were four buttons on the front: on/off/volume, horiz, vert, channel/fine tune. We had access to four local Boston stations (Channels 5, 7, and 9) as well as WGBH (Channel 2, the nation’s first public television station) and fuzzy, static-filled view of Channel 12 in Providence if we were desperate. Sometimes, during the middle of the day, there was nothing to be found on the screen except a test pattern. In the early mornings there was Today with Dave Garroway and his monkey, J. Fred Muggs. Mid-day there was news, the weather with Don Kent, and my mother’s soap operas. There were only a couple of shows for kids: Howdy Doody and The Mickey Mouse Club weekdays and The Lone Ranger on Saturday. As a rule, the family watched television together (after all, there was only one television set in the house). We tuned into the same legendary shows as everyone else: Father Knows Best, I Love Lucy, The Life of Riley, The Jackie Gleason Show (with the June Taylor Dancers and The Honeymooners), The Ed Sullivan Show and of course Walt Disney Presents.

Commercials were not nearly as frequent as they are today. The most memorable were for cigarettes: a synchronized Rockette style kick line of Chesterfields; a bellboy shouting “Call for Philip MoRISS!”; and an incomprehensible tobacco auctioneer spieling ever higher bids, then intoning, “Sold! American Tobacco!” followed by the calm pronouncement, “Lucky Strike means fine tobacco.”

Some industries were way too staid for such marketing shenanigans. They tended to sponsor the more serious programming that our parents watched as we kids busied ourselves with coloring books, or jigsaw puzzles, or retreated in disgust to our rooms to read books. The sponsors of Omnibus and The Alcoa Theater ran ads that were as dull as the programs (I used to think). Except for Cavalcade of America. I remember nothing about the program—but I’ve never forgotten the tagline of its sponsor, DuPont: “Better Things for Better Living Through Chemistry.” It was a convincing claim back in the 1950s. Today? Not so much.

![]() Today we know better. Because we know about the damage done by napalm, and RoundUp , and the granddaddy of them all: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Ah, DDT! Our neighborhood bordered Pine Tree Brook, a tributary to the Neponset River that flows into Boston Harbor. I remember being among a group of kids running behind the small plane that sprayed this sweetish smelling cloud of poison over every yard on our street. That’ll teach those mosquitoes!

Today we know better. Because we know about the damage done by napalm, and RoundUp , and the granddaddy of them all: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Ah, DDT! Our neighborhood bordered Pine Tree Brook, a tributary to the Neponset River that flows into Boston Harbor. I remember being among a group of kids running behind the small plane that sprayed this sweetish smelling cloud of poison over every yard on our street. That’ll teach those mosquitoes!

In truth, the mosquitoes learned nothing. We were the ones who did the learning. Thanks to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, we learned that in trying to outsmart Mother Nature, we had actually outsmarted ourselves.

For the chemicals we had been told were “better things for better living” were not, in fact, making life better. DDT, for one, was destroying the environment—killing birds, bees—and sometimes even us. It would be ten years, before the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), banned its use.

This is Now

Meanwhile, industrial companies had been using the ocean as a dumping ground for decades. In 1972, the same year DDT was banned, Congress passed the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act. But too late.

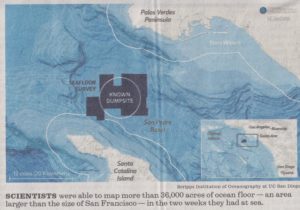

![]() Today, with my morning coffee, I learned that between 350 and 700 tons of DDT now rest in barrels on the seabed about 12 miles off Los Angeles, between Palos Verdes and Catalina Island. The long-term impact of this undersea toxic dump is unknown. What is known is that DDT is harmful to humans and has been linked to cancer in marine mammals.

Today, with my morning coffee, I learned that between 350 and 700 tons of DDT now rest in barrels on the seabed about 12 miles off Los Angeles, between Palos Verdes and Catalina Island. The long-term impact of this undersea toxic dump is unknown. What is known is that DDT is harmful to humans and has been linked to cancer in marine mammals.

As it happens, Point Vicente on the Palos Verdes peninsula is one of our favorite places. When looking out over spectacular views of Catalina Island from this spot, I’ve often thought that it’s no wonder Magellan named this ocean “Pacific.”

From now on, unfortunately, I’ll never be able to look out at that view again without being painfully aware of those unseen barrels of poison, 3,000 feet down.

“Better things for better living through chemistry”?

I don’t think so.