The Eclipse. The Gun. And Possibly, the Bottle in the Back Room.

This family legend is excerpted from my upcoming book:

Lighter Than Air: The 20s, The 30s, The War, and a Marriage Made in Heaven

…a compilation of the stories told (and retold) by my Uncle, Joe Flynn.

~~~

In January of 1925, a total eclipse of the sun was predicted, and storekeepers everywhere were nervous. For some reason, the Police decided to issue warnings that robbers might decide to take advantage of the darkness in the middle of the day and stage holdups.

In January of 1925, a total eclipse of the sun was predicted, and storekeepers everywhere were nervous. For some reason, the Police decided to issue warnings that robbers might decide to take advantage of the darkness in the middle of the day and stage holdups.

Lester Walsh, the manager at the A&P, where George worked (every day after school and on Saturdays), was alarmed by these warnings. Well, Lester Walsh had a gun, which he planned to stash on the shelf under the cash register for protection against these potential robbers.

Maybe before putting his gun on the shelf, he decided to clean it. Or load it. Anyway, there he was “fiddling around with his gun” (as he later explained it) when it went off.

In those days butter was delivered in large tubs and was measured out into one-pound packages in the stores. So there was my brother George in the back room measuring out butter when the bullet from Lester Walsh’s gun tore through him.

Meanwhile, back at home, it was just a normal Saturday afternoon. Ma wanted me to go up to Columbian Square to pick up a few things at the A&P. And Pa had told me to stop at the newspaper store and get him the latest copy of his favorite magazine. As I was going out the door, Ma reminded me stop at the Mulligans’ house on White Street. Mrs. Mulligan was a widow and had a bed-ridden daughter. Whenever Ma sent me to the store, she always reminded me to see if Mrs. Mulligan wanted anything. So I headed off up the street, bundled against the raw New England winter, and dragging my sled behind me.

The Model T was in the garage, up on blocks. Back then, cars came off the road for the winter because driving in snow was just about impossible. Only the main roads were cleared of snow; on side streets there were only shoveled pathways barely wide enough for pedestrians to walk to the trolley stops. The trolley tracks were cleared and good for walking; but of course you had to climb up on a snow bank to get out of the way whenever a trolley came along.

Anyway, I stopped at the Mulligans; I went to Nash’s and bought Pa’s magazine. Finally, I arrived at the A&P. Well, Henry, the clerk, when he saw me–he could hardly speak. He told me George had been shot. I just couldn’t believe it. He said the lucky thing was that a customer who had just come in had a car parked out front, and he was able get to George right over to the hospital. Well, of course I didn’t bother buying any of the things I had been sent to get. I just turned around and ran out of there, ran all the way home, my sled bouncing along behind me. I got there so out of breath I couldn’t even get the words out. But Ma and Pa already knew. Someone had called from the hospital and they were putting on their hats and coats. I wanted to go with them, but they told me to stay home and help Mary and Margaret with the little boys. (John had just turned four, and Philip was only two.)

They told us later, that when they got to the hospital, two policemen were waiting; they had Lester Walsh with them. “Mr. Flynn, do you want to press charges?” the Police sergeant asked.

“I don’t care about this man,” Pa said, walking right past them all. “I just want to see my son.” So Lester Walsh never did get arrested.

The bullet had gone right through George’s upper torso and out through his back; they actually found it under him when they were first examining him in the hospital. It had gone through his liver, which was serious. It was touch and go for a while. Dr. Emerson operated on George. He must have done a good job because eventually George got better and came home.

The bullet had gone right through George’s upper torso and out through his back; they actually found it under him when they were first examining him in the hospital. It had gone through his liver, which was serious. It was touch and go for a while. Dr. Emerson operated on George. He must have done a good job because eventually George got better and came home.

Things weren’t the same for us while George was in the hospital. He was the one who always livened things up around the house. We all missed him. But the one who seemed to miss him most was Rover, our dog. Each night at suppertime, Rover would circle the table sniffing at George’s empty chair, then he’d walk to the kitchen door and back before collapsing on the dining room floor in disgust.

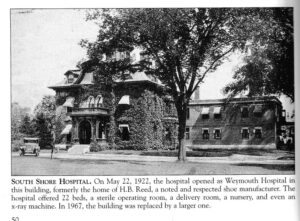

The dog was really upset. Mary and I discussed it. And we decided, maybe it would help if we could show him where George was. So the next Saturday, after George had been gone for a whole week, we took the dog and set off… up White Street to Union Street, across the Square and up Columbian Street. The hospital was in a mansion where people had been living up until two years before. The big front room was the main ward. It had floor-to-ceiling windows, and that made it pretty easy for us to see inside.

The dog was really upset. Mary and I discussed it. And we decided, maybe it would help if we could show him where George was. So the next Saturday, after George had been gone for a whole week, we took the dog and set off… up White Street to Union Street, across the Square and up Columbian Street. The hospital was in a mansion where people had been living up until two years before. The big front room was the main ward. It had floor-to-ceiling windows, and that made it pretty easy for us to see inside.

Mary and I pressed our noses against the window and rapped on the glass to catch George’s attention. He saw us and sat up. We waved and smiled, jumping with excitement, and George waved back. Sensing our excitement—or maybe sensing that George was nearby (who knows?)—Rover began to bark. Before too long, one of the nurses saw what was going on. She opened the heavy front door, put a finger up to her lips and waved us—and the dog—to come inside. Rover was ecstatic. He put his front paws up on the bed lapped George’s face. We were equally happy. We had a few minutes to hug George, and then the nurse told us, we’d better leave before we all got in trouble, including her.

We took our time walking back home. And all the way, the dog’s tail, as he followed along behind us, was going a mile a minute—a lot faster than our feet.

And, you know, I’ll bet that is probably the only time there was ever a dog inside the South Shore Hospital.”

George’s white A&P clerk’s jacket with bullet holes in the front and back, was neatly folded in a trunk in the attic. He brought it out to show everybody, whenever anybody started reminiscing about the day he got shot.

George had the bullet for years. After he recovered George went down to the police station and got the bullet. It was a 38. He kept the bullet—and the jacket for the rest of his life. I guess his grandchildren must have them now.

Pa’s sister, Mary Costello, was a lawyer; she asked Pa what he wanted her to do about the shooting. “Let the A&P pay all the bills,” he said. And that’s what happened. There was very little publicity. Lester Walsh was transferred to another store.

Pa’s sister, Mary Costello, was a lawyer; she asked Pa what he wanted her to do about the shooting. “Let the A&P pay all the bills,” he said. And that’s what happened. There was very little publicity. Lester Walsh was transferred to another store.

Seeing my brother get shot. That, even more than the incident with Mary and the air gun, made me decide I wanted nothing to do with guns.

I had already started working at the A&P before that day when George was shot. So I knew Lester Walsh had a gun. I knew he had a bottle in the back room, too.